Matthew 2:13-23

Now after they had left, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.” Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt, and remained there until the death of Herod. This was to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet, “Out of Egypt I have called my son.”

When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah: “A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.”

When Herod died, an angel of the Lord suddenly appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and go to the land of Israel, for those who were seeking the child’s life are dead.” Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother, and went to the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was ruling over Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there.

And after being warned in a dream, he went away to the district of Galilee. There he made his home in a town called Nazareth, so that what had been spoken through the prophets might be fulfilled, “He will be called a Nazorean.”

Three years ago, this commercial was released on Christmas Eve. Take a look.

It was not well received. It managed to anger people from across the political spectrum, from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Charlie Kirk. When that happens, I think a cord has been struck. Rarely do we see anything that unites people so quickly, even if it’s in shared frustration.

One of the outcomes of the commercial, intended or not, was a flurry of arguments about Jesus and the holy family. The most central question was whether Jesus was a refugee. People fixated on that word, that label.

Some said yes, absolutely. The text could not be clearer. Mary, Joseph, and Jesus fled persecution from a violent ruler who threatened their lives. Under cover of night, they made a dangerous escape to another land. How could that not describe a refugee?

Others so badly wanted—and still want—to refute the claim and make sure Jesus does not wear the name refugee. The argument goes Egypt was under Roman control, just like Bethlehem. So technically, they didn’t cross a national border. Therefore, Jesus was not a refugee. At most, the holy family could be called internally displaced persons.

Which… ah yes, that sounds so much better.

What a pointless, trivial argument, for several reasons.

First, Matthew knew nothing of our modern categories: refugee, internally displaced person, asylum seeker, or anything else. He is not interested in our labels.

Instead, Matthew is doing something much bigger. He is positioning Jesus as the new Moses,

the chosen one of God who will save Israel and lead God’s people into freedom once again.

That’s why this story echoes the exodus: a power-hungry ruler threatened by a child, violence against the innocent, a flight to and from Egypt, and finally a settling in the land promised by God.

But most of all, Matthew is showing us the providence of God. God warns. God directs. God protects. From the very beginning, this child’s life is carried by God’s faithful care, revealing him as the fulfillment of God’s promises to Israel.

All of that matters for Matthew’s audience and for us. But equally important to the theological claim, and something easily overlooked by people like me who haven’t had this experience,

is the fact that Jesus’ life and ministry were shaped by forced migration.

By being on the run. By a dangerous journey away from violence and toward whatever safety could be found in a foreign land.Most of us have no idea what that is like—to leave everything behind, to be that vulnerable, to live at the mercy of strangers in a strange land.

There are all sorts of stories that tell us about the dangers migrants face on their journeys.

One of the most illuminating I’ve read comes from Caitlin Dickerson’s cover article in The Atlantic called “Seventy Miles in Hell.”

Dickerson and a photographer, Lynsey Addario, traveled alongside families as they crossed a perilous jungle passage known as the Darién Gap: a stretch of wilderness between Colombia and Panama that, in recent years, has become one of the most common and dangerous routes toward Central America and, eventually, the United States.

Dickerson introduces us to a family she meets at the beginning of the journey. Bergkan and his partner Orlimar are from Venezuela, not yet married, parents to two children: Isaac, who is two, and Camila, eight.

This was never the life they imagined. Their dream was to build a future in Venezuela, but poverty and persecution forced them to leave. So they formed a new dream and took drastic measures to make it possible.The night before they set out, Bergkan voiced his fear: What if someone gets hurt? What if a child gets sick? What if someone is bitten by a snake—or worse?

On the very first day, sharp inclines tore their shoes. After carrying his two-year-old all morning, along with his partner’s bag, Bergkan collapsed to the ground, already exhausted, physically and mentally. He emptied the bag, leaving behind what little they had: old headphones, sandals, a couple pairs of shoes.

Along the way, porters offered goods and services at steep prices: five dollars for a bottle of water, a hundred dollars an hour to carry a bag or a child. The journey had already cost the family a thousand dollars per person, with no guarantee they would survive it. Each day brought new threats.

The camps were riddled with scams, fear of sexual assault, and the risk of kidnapping. The family eventually made it out of the jungle, but what they witnessed stayed with them: hungry travelers begging for food, nearly naked people desperate for clothing, sick children unable to go on. We don’t know what ultimately happened to this family. The last update placed them in Mexico City, unsure of what came next.

It was a dream that drove Joseph and Mary to drastic measures too. We’re given no details about their journey. But if stories like Bergkan and Orlimar’s tell us anything, it could not have been easy. Were porters offering their services along the way? Were they robbed of the gold, frankincense, and myrrh they had just received? Did Mary face the threat of sexual assault?

Did Joseph collapse from exhaustion, carrying his child and his partner’s belongings?

We’re told nothing about the years the holy family spent in Egypt. No details. No stories. Just silence.

Did Joseph struggle to find work? Did people resent him for it—muttering that he was taking jobs that belonged to someone else? Did they struggle with the Demotic language and told to just learn it? To adapt faster? To be grateful they were there at all?

I have to believe that all of that shaped Jesus’ life and ministry—that when later he spoke about feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, caring for the sick, and welcoming the stranger he was not speaking in abstractions.

“What you do—or fail to do—to the least of these, you do to me. Because it was me and my family.”

All of it presses the same truth into us: the holy family did not just flee danger—they also lived the hard, unseen reality of being immigrants.

If we had been there—if we had seen the holy family on the road to Egypt—I think we’d like to believe we would have helped them. That we would have offered water. Food. A place to rest. Somewhere safe to stay along the way.

We imagine ourselves as the ones who would welcome them in, who would protect a frightened mother and a vulnerable child, who would offer dignity after such a perilous journey.

So why do we not do the same now—for the struggling, suffering migrants who, following a dream, flee violence and traverse hell to get here, just as the Holy Family once did?

Today, instead of recognizing them, we scapegoat people like them. We call them garbage and their countries hellholes. We create policies not just to deter migration, but to make it harsher, more painful, more dangerous.

Matthew forces us to see Jesus and the holy family in every family that follows a dream, that flees persecution, that escapes some kind of hell, and is forced to settle in a new land.

Arguing about whether Jesus was a refugee or not is a waste of time. What matters is how we treat the people today who find themselves in the same situation the holy family faced two thousand years ago. What we do to people today, we do to them

I understand that immigration policy is complex. But what should not be complex is our commitment to dignity—especially in the way we talk about migrants and the way we respond to their suffering.

We live this faith by putting our bodies, voices, and resources where our prayers are.

By supporting organizations like Exodus Refugee and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, who walk with families long after the headlines fade. By advocating for higher refugee admissions and humane conditions that honor the dignity of every person. And by praying in ways that change us—for all those fleeing violence, escaping hell, and daring to believe there might be life on the other side.

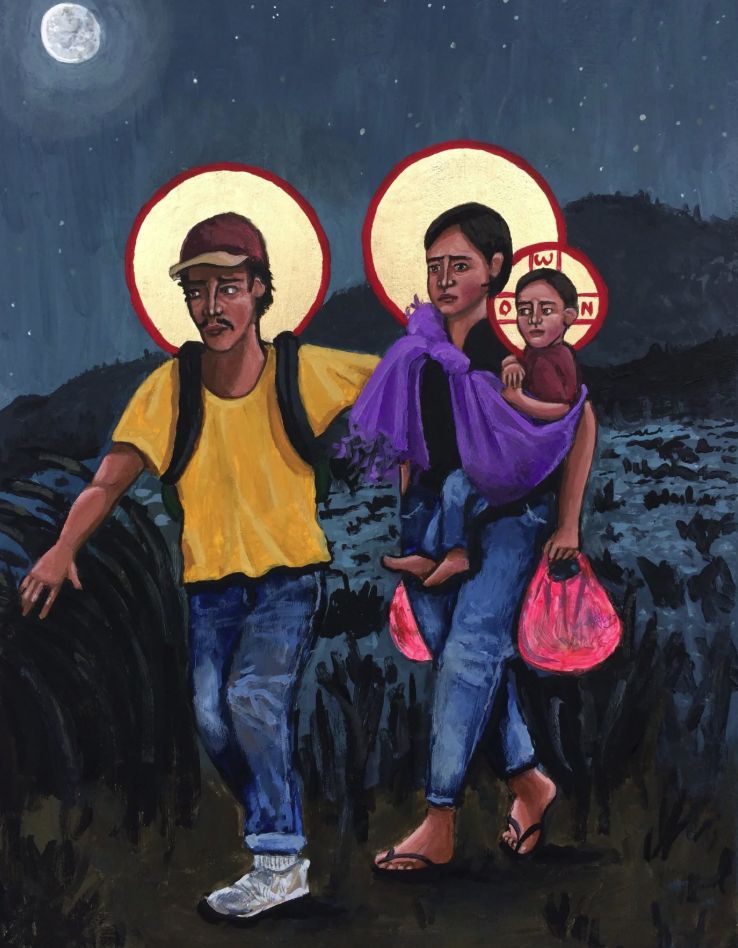

Icon by Kelly Latimore

We meet Jesus and the holy family in every person who follows a dream to a new land. How we treat them reveals what we believe about him.

Merry Christmas. Amen.