Matthew 5:1-12

When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up the mountain; and after he sat down, his disciples came to him. Then he began to speak, and taught them, saying:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account.

Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

I like to be right. Just ask Katelyn. Or better yet, ask Pastor Mark when he points out a grammatical error in my writing. Yes—the Oxford comma should be there.

What’s worse than liking to be right is having a toddler who also likes to be right. I hold up an orange and he declares it an apple. I say it’s too cold to go to the park and he responds, “No it’s not—it’s perfect!” You get the picture.

I imagine I’m not alone in this. We all like to be right. And our certainty—our confidence that we are right—can be far more dangerous than we realize.

In 2008, a woman went to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard teaching hospital, one of the best in the world. She’s taken back to the OR, put under, and the surgeon completes the surgery successfully. Everything went great…Until she woke up in recovery and realized the wrong side of her body had been stitched up.

The surgeon had operated on her left leg instead of her right.

When the hospital later explained how this happened, Kenneth Sands, a vice president, said this: “The surgeon began prepping without looking for the mark and, for whatever reason, he believed he was on the correct side.”

We’ve all felt utterly right about something, only to discover later that the opposite was true. And more than we like being right, we hate realizing we’re wrong. Now, an important clarification - Being wrong and realizing you’re wrong are not the same thing.

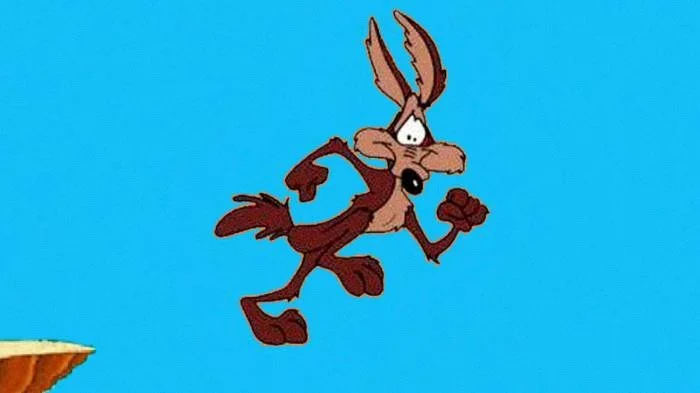

Kathryn Schulz uses an image from Looney Tunes to explain this. Wile E. Coyote chases the Road Runner straight off a cliff. He keeps running, completely confident, even though there’s nothing beneath him. It’s only when he looks down that he realizes he’s in trouble.

That’s the difference. Being wrong is standing over thin air and thinking you’re on solid ground.

Realizing you’re wrong is looking down and seeing there’s nothing holding you up.

This morning, I want to linger with just two of the Beatitudes. Not because the others don’t matter—but because these two speak directly to the world we’re living in right now. Our longing to be right, and our deep resistance to admitting we’re wrong, sit at the heart of so much division: in our homes, our communities, our churches, our nation, and even within ourselves.

And into that reality, Jesus speaks a word of blessing—a word that turns our fear, our hatred of being wrong into good news.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. We know what it means to be hungry and thirsty. Those longings are part of being human. We hunger not only for food, but for connection, purpose, community, beauty, and joy.

But to hunger for righteousness? That’s not a phrase we use or even hear outside of this space. In fact, it’s a word many of us avoid. It can sound pious, self-righteous, or just plain uncomfortable.

And that’s unfortunate… Because our discomfort with the word comes from confusion about what it means. Righteousness simply means being made right: made right with God, made right with others, and made right with yourself. Blessed, then, are those who long to be made right.

Like the other Beatitudes, this one surprises us. Standing there on the mountainside, we might expect Jesus to say, Blessed are the righteous. Blessed are the ones who get it right. Blessed are the ones who already are right.

But that’s not how it goes. When people come to Jesus assuming they are righteous, he has a way of setting the record straight. It is those who come knowing they are wrong—those who long to be made right—who receive grace and mercy.

The truth of the matter is this: we cannot make ourselves right with God, no matter how hard we try.

All the praying, Bible reading, worshiping, serving, and learning in the world do not make us righteous before God. Rather, the Holy Spirit works through these practices to make us aware of the grace of Jesus. And that grace alone is what makes us right. Not our words nor our posts on Facebook. Not our deeds. Not our politics. Grace alone.

Which is why Jesus finishes the Beatitude in the passive voice: for they will be filled.

Those who recognize they are wrong, those who don’t always get it right, those who long to be made right rather than clinging to the certainty that they already are - they will be filled. They will be made right with God, with others, and themselves.

This is a blessing for those of us who get it wrong—who mess up, who don’t always get it right.

So much of what we see and hear around us—in our culture, in business, certainly in politics—tells us to do the opposite: never admit fault, double down, point fingers, claim victory at all costs, and insist that we are always right. But there is no hunger or thirst to be made right if we never admit that we’re wrong.

This blessing is for those who screw up - and can say so.

What if this was our posture in the present moment, instead of the certainty that we are right?

What if we moved through the world not with the desire to be right, but with the desire to be made right—not only with God, but with one another? What if we faced our spouses, our kids, our neighbors with the simple possibility that maybe… I’m wrong on this.

Believe me, I’m preaching to myself here. How much better would your marriage be? Your relationship with your kids? How many friendships might be healed if we could say, “I was wrong. I’m sorry. I want this to be made right.”

To error is to be human. So be human, admit you’re human, and be blessed.

And the best news comes with the Beatitude that follows: Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

Jesus meets our wrongness—our sin, our failure, our getting it wrong—not with contempt, not with an I told you so, but with kindness. With mercy. In this life, we expect being wrong to be met with punishment. But Jesus shows us another way. Instead of meeting our sin with punishment, he meets it with sacrifice, generosity, and mercy.

And it is only because we have received mercy that we can extend mercy to others.

We cannot give what we have not first received.

So when someone comes longing to be made right—admitting they were wrong—it does no good to meet that honesty with harsh contempt or punishment. We resist this because we’re afraid. Afraid mercy will be taken advantage of. Afraid kindness will be trampled on.

And yet, what does the Lord require of us but to love kindness.

We don’t need to hate being wrong. Because when we admit we’re wrong, we are not earning grace—we are simply telling the truth. And grace is already there to meet us.

This week: look for one moment—just one—where you can say the words, “I was wrong. I’m sorry. I want this to be made right.” Say it to your spouse, your child, your neighbor, your pastors, or to God.

Don’t refute. Don’t double down. Don’t defend yourself. Instead, hunger and thirst to be made right.

And then be surprised by the grace of Jesus that meets you there, fills you up, and says, I forgive you.

In a world where leaders and institutions seem incapable of doing such a thing, this may be one of the strongest witnesses Christians can do in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, who gives us mercy, makes us right, and blesses us: not in spite of our mistakes, but because of them.

Amen.